DATA-150---Jtao

Research Proposal

Jialu Tao

Word Count(without references): ~ 2000

Introduction

Increasing large-scale development of infrastructure projects not only have benefits but also negatives. To prevent, mitigate, and control potential negative environmental and social impacts, the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), a decision-making tool, is introduced to inform development decisions by mandating consideration of alternatives and ways (Jennifer, 2008). One part of the EIA is about resettlement and dislocation of people living there caused by the construction of infrastructures because of the need for land. Even in situations where people are not required to physically move, the project may still impact their livelihoods or income-generating activities (IFC 2002), or cause other environmental and social impacts that make continuing to live there untenable. Project-induced resettlement can occur on a massive scale and is sometimes considered as being ‘projects within projects’ (Reddy et al, 2015). For example, there were nearly 1.13 million people had to be relocated to the Three Gorges Dam in China. The thing is despite the various guidelines and standards, in almost all projects, people who were resettled were made worse off (Vanclay, 2017). Extensive works have focused on how improvements in regulations and guidelines may help project-induced resettlement. In this passage, I will instead focus on how utilizing machine learning may help the profiling and baseline data collection stage and then improve the overall project-induced resettlement which may possible to make people better off.

Challenges

Although the EIA process is regarded as a first and foremost decision-making aid, we still face many obstacles that will frustrate the effectiveness of this process. One of the most salient ones is EIA exercise is often conducted late in planning, often long after project proponents have become attached to a particular design concept (Leonard & Anne, 1995). However, conducting late in planning can only allow EIA to propose the potential mitigation measurement instead of mandating consideration of alternatives. As Ensminger and MacLean (1993: 49-49) have pointed out, “major decisions, including the action to be carried out and its location, are often made before the EIA is prepared and … the EIS is then drawn up to support those decisions.” One of the reasons may because EIA is an extremely slow process. It may take a minimum of 210 days long for an entire process with the addition of 60-80 days in case of rejection and accounting for the typical bureaucratic delays. Thus, many project proponents would deem it irrational and a waste of time and money to conduct EIA before a project is well-defined and there is a high likelihood that it will be funded and approved (Nelson 1993 and Hirji 1990). However, although the benefits of dam construction are numerous, serious negative environmental, human, and political consequences can outweigh the benefits, such as the Tehri Dam in India. The thing is the problematic decisions will affect countless people’s lives. There are 24,000 people displaced because of the Tehri Dam who have not been provided with land rights, nor do they have basic amenities (2015). This kind of tragedy is possibly be avoided if the EIA process is done before the major decision.

With the development of spatial technology, profiling, and baseline data collection for project-induced resettlement will be more and more accurate. However, the data collected are problematic is one of the main issues in past projects. The reliable data that need to be collected are: the number and types of people to be resettled; the number and types of buildings and other assets that will be affected; community infrastructure and common property resources; the socio-economic situation of the affected community (including their health, education, skills, etc.); their community and political structures; tenure arrangements and land entitlements; the basis of people’s livelihoods; and their key issues of concern (Vanclay, 2017).

The problematic data used as the foundation of the whole project can aggravate the already severe situation. There is a consensus that there is a gendered dimension to the negative effects of resettlement and this has been explored in-depth in the literature (Hay et al. 2015). For example, unmarried women may only get access to land and other resources in the resettlement process through a man, or after a certain age (Bisht, 2009, p 313) or women in resettlement areas of Tehri Dam (India) were less able to contribute to the household and spent their time alone in small houses rather than working outdoors and meeting other women which contributes to anxiety and poor mental health (Asthana 2012; Bisht, 2009). Another reason why people are always worse off after the project-induced resettlement is about indigeneity. Forced displacement tears apart the existing social fabric: it disperses and fragments communities, dismantles patterns of social organization and interpersonal ties; kinship groups become scattered as well.

Three Gorges Dam

The Three Gorges Project (TGP) on the Yangzi River in China is the world’s largest hydroelectric power project. This completed system encompasses a dam, two powerhouses with a total of 22,500 MW of hydropower generation, and around 100 billion kilowatts which accounts for 2.5% of the national power generation a year. The power generated by the Three Gorges Project is equal to twenty times the power of Hoover Dam. Also, TGP plays an important role in river navigation which in 2006, 50 million tons of cargo passed through the new lock system up to Chongqing. Another major benefit of the project is improved flood protection of the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River (Peter, 2009). By providing flood storage space, the dam reduces the potential for floods downstream, possibly affecting millions.

However, such projects are growing in their potential to displace massive numbers of people and will continue to yield a range of environmental consequences in the affected countries or regions in the near future (Cernea, 2008). Duncan A Rouch (2019) compares the original EIA report with the actual and concludes that the original EIA report substantially underestimated outcomes in displacement and land carrying. Besides the total number of people who need to be resettled, another problem is where will the migrants move to. There are three major approaches for resettlement: settling in nearby areas, moving far away, and moving to urban enterprises. In the research conducted by Li Heming and Philip Rees (2000), they argue that the approach which settling in nearby areas is favored by TGP’s planners because it can prevent labor from flowing out of the local area, help promote the project and avoid potential issue affecting social stability. However, the arable slope land should be only 300,000 mu (1 mu = 0.067 ha) rather than 4 million mu as the planners initially suggest (Chen et a, 1995). This is because the original EIS Report optimistically estimated that the carrying capacity of the land in the rural areas could support 1 million rural resettles (Xu et al., 2013).

The human carrying capacity of the environment in the TGRA (Three Gorges Area) is a key factor in devising resettlement policies and schemes. The overestimation has caused the displacement of about 190,000 rural residents to be resettled in 11 provinces during 2000-2008 (Xu et al., 2013). Indeed, predicting the carrying capacity to the environment in the reservoir area is difficult. Take several key factors into account is important, such as demographic change, environmental change and constraints of local resources, change in consumption, and change in food markets (Xu et al., 2013). To improve the calculation of human carrying capacity, I will use decision tree classifiers to identify the different types of land, and The Markov chain and Cellular Automata (CA-Markov) model to predict the land cover change. By using these two models we can estimate the land potential productivity and then compares this with the observed one. Although what is done is done, we can learn from the past and prepare for the future.

Data and Methodology

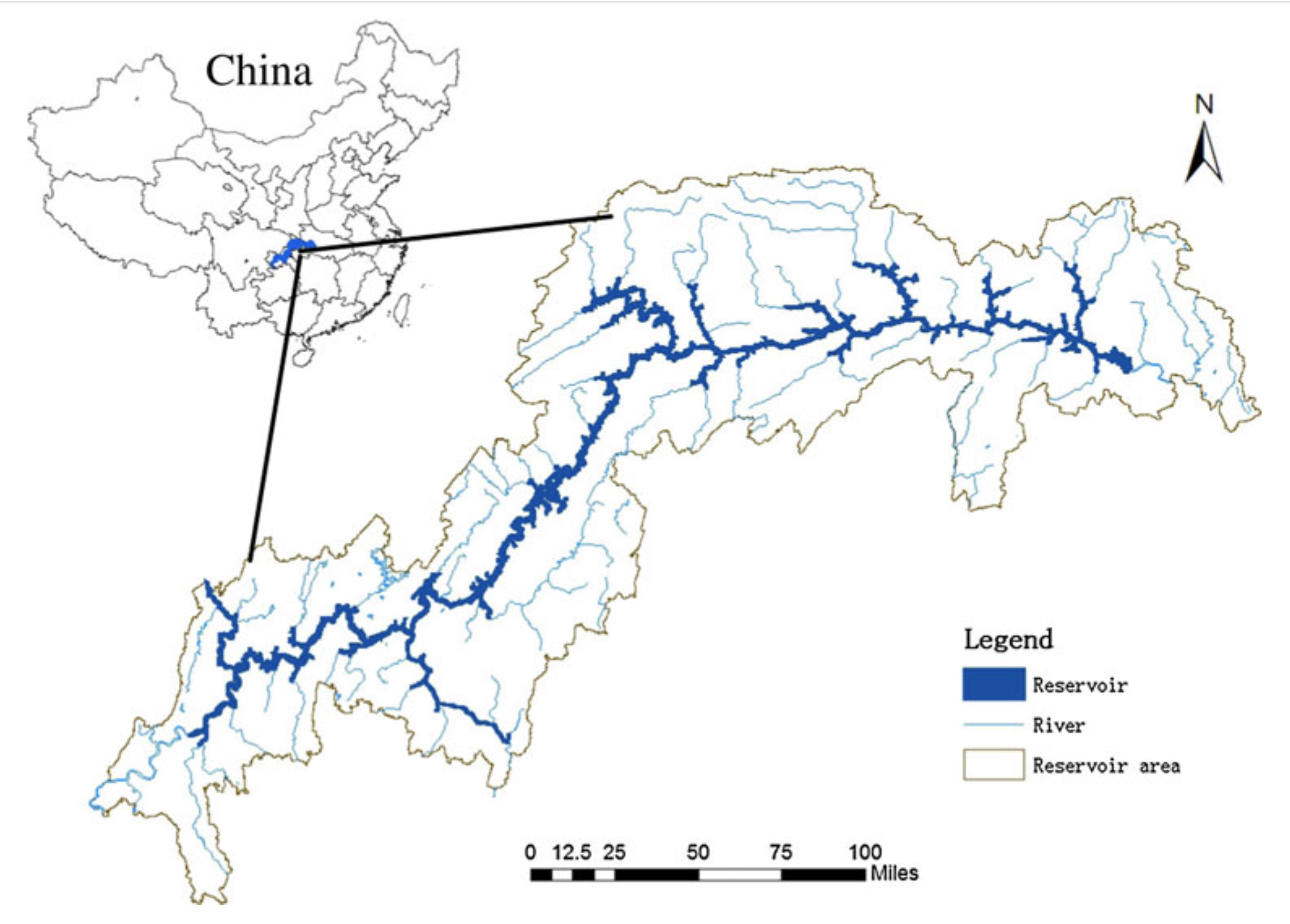

Firg. 1

Location map of the Three Gorges Reservoir area

source: Zhang et al., 2012

source: Zhang et al., 2012

The study area of TGRA is located between E106°160– E111°280 and N28°560–N31°440 (Fig. 1), covered the lower section of the upper Yangtze River, with an area of 58,000 km2 and a population of almost 20 million (Meng et al. 2005). The data we use for cropland mapping at a scale of 1:50,000 is Landsat/ CBERS images with a resolution of 30m for 1993 which is a year before the beginning of the construction of TGP. Because of the limited revisit period and a swath width of high-spatial-resolution satellite sensors and other effects, such as cloud coverage, it is always beneficial to apply various viable spatial resolution images from the different sensors (Liu et al., 2018). Thus, we will also require SPOT multi/pan images with 10m resolution, and SPOT 5/ALOS multiple spectral images with 10m resolution. In addition, to improve the accuracy of the cropland identification and mapping, ancillary data of DEM (digital elevation model) with a resolution of 10m will be referred to (Zhang et al., 2012). DEM is essential for doing radiometric and geometric corrections for terrains on the remotely sensed imageries (Gandhi et al., 2016).

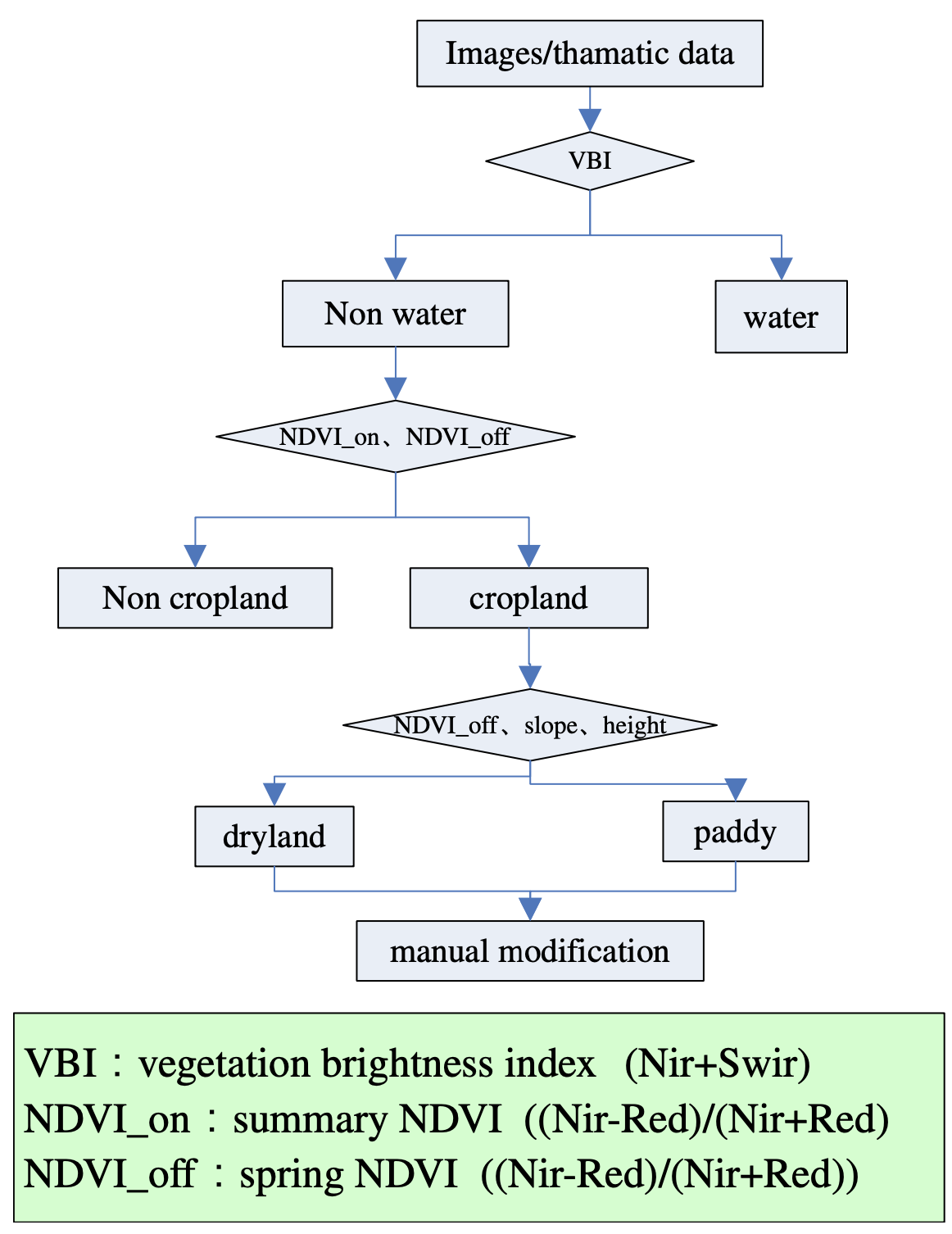

Figure 2

Framework of decision tree algorithm for cropland classification

source: Zhang et al., 2012

source: Zhang et al., 2012

The decision tree classifier was used with the index of VBI, NDVI_on, NDVI_off, slope, and elevation which is meaningful to the identification of cropland (Fig. 2). The primary idea of cropland retrieval was cropland identification from natural vegetation and bare areas(Zhang et al., 2012). NDVI is a vegetation index that is associated with vegetation density. It is often used to distinguish vegetation from non-vegetation features which normalize the difference between the green leaf scattering in the near-infrared to the chlorophyll absorption. Unlike conventional statistical and neural/connectionist classifiers, which use all available features simultaneously and make a single membership decision for each pixel, the decision tree uses a multi-stage or sequential approach to the problem of label assignment (Mather & Pal, 2003).

The Markov chain and Cellular Automata (CA-Markov) model is used to predict the Land cover change in TGRA. This model effectively combines the advantages of the long-term predictions of the Markov model and the ability of the Cellular Automata (CA) model to simulate the spatial variation in a complex system, and this mixed model can effectively simulate land cover change (43). It has advantages such as its dynamic simulation capability; high efficiency with data, scarcity, and simple calibration; and ability to simulate multiple land covers and complex patterns (36).

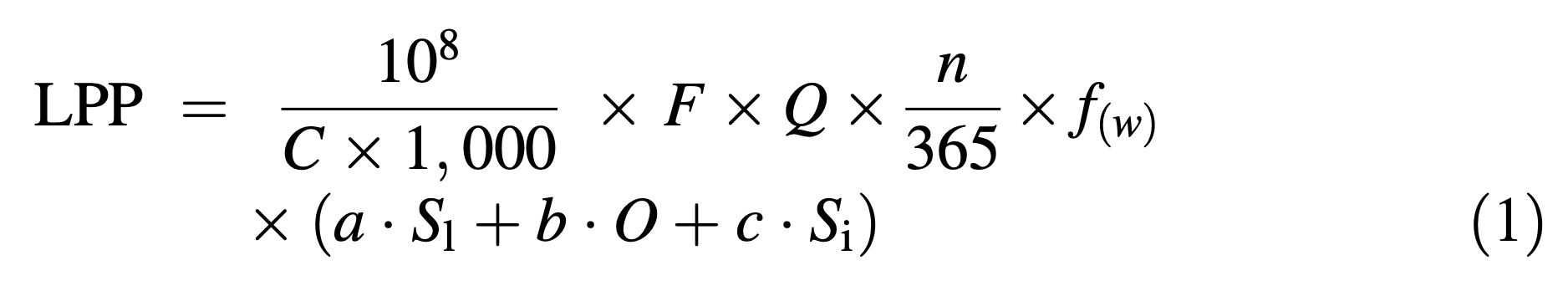

Land production potential (LPP) estimation is based on the conversion of plant energy and heat. The LPP is employed in the assessment of food production capacity. It represents maximum food production potential under natural conditions. LPP: Land production potential, kg/ha; C: dry material heat the chemical burning the energy of 1g dry matter, the majority of crops average C is 4.25 kcal/g; F: utilization the efficiency of sunlight energy; Q: annual solar radiation, kcal/cm^2; n: frost-free days through 1 year; f(w): ratio of precipitation to evaporation; r: annual precipitation, mm; E0: annual evaporation, mm; S1: assigned score of cropland slope; O: assigned score of soil organic matter content; Si: assigned a score of soil granule; a, b, c: weight value of soil conditions (Zhang et al., 2012).

Supposition and Implication

For CA-Markov model, calibration and validation is an important step in the process of the model prediction. The usefulness of a model depends on the output of the validation model (Liping et al., 2018). The Kappa index is one of the most popular used methods for quantifying the predictive power of a model (Singh et al., 2017). That is to compare the predicted data with reference data using the VALIDATE module. Using the CROSSTAB module in IDRISI, the predicted LULC of 1992 is compared with the 1992 observed results to obtain the Kappa index (Liping et al., 2018). When the Kappa index is acceptable, then we can use this to predict the results in 2007 and estimate the land potential productivity.

There are several limitations for the CA-Markov model that it doesn’t take into account the socio-economic factors such as the population growth, owner’s willingness to cover land, and change in land land-use policies during the period of simulation (Subedi et al., 2013). The prediction model should be adjusted and take socio-economic factors into account until the predicted land production productivity is similar to the observed one. Around $150,000 is used to conduct the whole project.

Conclusion

Dismissing the negative social impacts of resettlement as being ‘acceptable collateral damage’ or a ‘necessary evil’ to achieve national development is inexcusable. Thus, learning from past experience is extremely important which will not let the burden fall more those people who need to be resettled and even make it possible for them to better off ad not only thrive but also thrive.

Reference

Asthana, V. (2012). ‘Forced displacement: a gendered analysis of the Tehri Dam Project’. Economic and Political Weekly 47(47/48), 96–102.

Bisht, T.C. (2009). ‘Development-induced displacement and women: the case of the Tehri Dam, India’. The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology 10(4), 301–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/14442210903271312

Cernea, M., 2008. Compensation and Investment in Resettlement: Theory, Practice, Pit- falls, and Needed Policy Reform. In: Cernea, M., Mathur, H.M. (Eds.), Can Compensation Prevent Impoverishment? Oxford University Press, New Delhi, pp. 147–179.

Chen GJ, Xu Q, Du RY. 1995. Sanxia Gongcheng dui shengtai yu huanjing de yingxiang ji duice yanjiu (Impact of the TGP on environment and Solution). Science Pres: Beijing, China.

Gandhi, S. M., & Sarkar, B. C. (2016). In Essentials of mineral exploration and evaluation (pp. 53–79). essay, Elsevier.

Hay, M., Skinner, J., and Norton, A. (2019) Dam-Induced Displacement and Resettlement: A Literature Review. FutureDAMS Working Paper 004. Manchester: The University of Manchester.

Heming, L., & Rees, P. (2000). Population displacement in the Three GORGES Reservoir area of the Yangtze River, central china: RELOCATION policies and MIGRANT VIEWS. International Journal of Population Geography, 6(6), 439-462. doi:10.1002/1099-1220(200011/12)6:63.0.co;2-l

He D, Zhou J, Gao W, Guo H, Yu S, Liu Y. An integrated CA-markov model for dynamic simulation of land use change in Lake Dianchi watershed. Beijing Daxue Xuebao (Ziran Kexue Ban)/Acta Scientiarum Naturalium Universitatis Pekinensis. 2014;50(6):1095–105.

Hirji, R. F. 1990. Institutionalizing Environmental Impact Assessment in Kenya. Stanford University PI).D. dissertation. Stanford. CA.

IFC. 2002. Handbook for preparing a resettlement action plan [Internet]. Washington (DC): International Finance Corporation.

Lei, Z., Bingfang, W., Liang, Z., & Peng, W. (2012). Patterns and driving forces of cropland changes in the Three Gorges Area, China. Regional Environmental Change, 12(4), 765–776. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-012-0291-8

Liu, Q., Huang, C., Liu, G., & Yu, B. (2018). Comparison of CBERS-04, GF-1, and GF-2 Satellite Panchromatic Images for Mapping Quasi-Circular Vegetation Patches in the Yellow River Delta, China. Sensors, 18(8), 2733. https://doi.org/10.3390/s18082733

Li, J.C. (2008). Environmental Impact Assessments in Developing Countries: An Opportunity for Greater Environmental Security? https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Environmental-Impact-Assessments-in-Developing-An-Li/82173ed5ba23c8198c21bb653464a3866ade0942

Liping, C., Yujun, S., & Saeed, S. (2018). Monitoring and predicting land use and land cover changes using remote sensing and GIS techniques-A case study of a hilly area, Jiangle, China. PloS one, 13(7), e0200493. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200493

Meng JJ, Shen WM, Wu XQ (2005) Integrated landscape ecology evaluation based on RS/GIS of Three-Gorges Area. Acta Scientiarum Naturalium Universitatis Pekinensis 41(2):295–301 (in Chinese)

Nelson. R.E. 1993. “A Call for a Return to Rational Comprehensive Planning and Design.’’ In Environmental Analysis: The NEPA Experience, 66-70. S.G. Hildebrand and J.B. Cannon. eds. Boca Raton FL: Lewis Publishers.

Ortolano, L., & Shepherd, A. (1995). Environmental impact assessment: Challenges and opportunities. Impact Assessment, 13(1), 3-30. doi:10.1080/07349165.1995.9726076

Pal, M., & Mather, P. M. (2003). An assessment of the effectiveness of decision tree methods for land cover classification. Remote Sensing of Environment, 86(4), 554–565. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0034-4257(03)00132-9

Reddy, G., Smyth, E., & Steyn, M. (2015). Land access and resettlement: a guide to best practice. Greenleaf Publishing.

Rouch, D. A. (2019) Role of Geographical Information Systems in Promoting Sustainable Agriculture, Working Paper No. 8, Clarendon Policy & Strategy Group, Melbourne

Singh SK, Laari PB, Mustak S, Srivastava PK, Szabó S. Modelling of land use land cover change using earth observation data-sets of Tons River Basin, Madhya Pradesh, India. Geocarto Int. 2017:1–34.

Subedi P, Subedi K, Thapa B. Application of a Hybrid Cellular Automaton–Markov (CA-Markov) Model in Land-Use Change Prediction: A Case Study of Saddle Creek Drainage Basin, Florida. Science & Education. 2013;1(6):126–32. Vanclay, F. (2017). Project-induced displacement and resettlement: from impoverishment risks to an opportunity for development? Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 35(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2017.1278671

Xu, X., Tan, Y., & Yang, G. (2013). Environmental impact assessments of the Three Gorges Project in China: Issues and interventions. Earth-Science Reviews, 124, 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2013.05.007